|

To: |

|

To: |

![]()

![]()

![]()

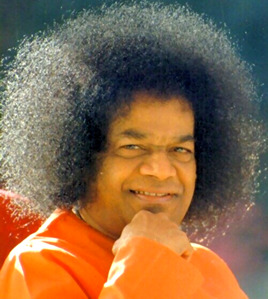

As learnt at

the Lotus Feet of Bhagavan

by

N. Kasturi (1897-1987)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

PART-II

PART-II Upanishad

means 'sitting near'. The pupil seated at the feet of

the Guru or Master listens reverentially to the

answers given in reply to his questions. One Upanishad

is appropriately named the 'Prasna

Upanishad'

(the question centred lesson) wherein Pippalada,

the Guru, directs six pupils in search of Brahmam.

"Dwell with me a year more with austerity, chastity and

sraddha. Then ask what questions you will. If I

know, I shall tell you all". Another of the Upanishads

has the interesting title, 'Kena'

(By Whom?). It starts with a series of three questions:

"By whom is the mind impelled? By whom is breathing

ordained? By whom is the tongue impelled to speak, the

eye to see, the ear to hear?" Most of

the other Upanishads disclose the fundamental

principles and processes of spiritual inquiry through

dialogues between the Gurus and their disciples. We

notice a wide disparity among these disciples both in

levels of scholarship and in social status-kings and

millionaires, aristocrats as well as the sons of

commoners, teenage as well as adult aspirants, women and

gods like Indra. The instructors too were varied -

cartmen and kings, sages, recluses, warriors and women,

saints like Yajñavalkya and gods such as

Prajâpati and Yama. Devotion,

as it wells up within us, exhilarates, for we are then

'in the light', but inquiry, and its fruit, knowledge,

exterminate us, for we merge in that light. This is the

reason why Yajñavalkya, at the end of a prolonged

bout of question and answer with Gargi, a dogged

disputant, a formidable dialectician and a widely revered

guru, advised her, "Gargi! Do not question too much, lest

your head fall off! In truth, you are questioning too

much about Brahmâ of which further questions

cannot be asked. Gargi! Do not over-question." Thereupon,

says the Brihadaranyaka

Upanishad,

Gargi held her tongue. Swami

too concludes the dialogue with the bhakta,

forming the Sandeha

Nivarini,

with this same answer to the final question. "Without

spending time on such un-understandable problems, engage

yourselves in the things you urgently need, traversing

the path which will lead you to the goal." Once you

take off into space, soar beyond paths into the pathless,

questions cease and answers are lived, not learnt. The

mind cannot reach that realm of reality. All attempts to

encase that experience in words are futile. The

jñâna marga is really easier than the

bhakti marga," Swami has said, "for a

revelation, an awareness of the truth can occur in a

flash to those who are able to sit quiet for a few

minutes and analyse themselves!" There

is one more hurdle: "the better acts as the enemy of the

best". The sâdhana might reveal that the

sâdhaka is the supreme and this feeling

might confer great joy. He would be happy that he has

attained the goal, acquired the treasure, achieved

victory. But, Swami says, "The rasa or sweetness

of this subject-object samâdhi (I - He

sameness) is a temptation one has to avoid, for it is

only the second best. The joy is just enough to act as a

handicap (rasa-aswadana - enjoyment of bliss).

Direct perception of one's reality as Brahman, the

awareness of oneself as the cosmic Self, happens in a

flash when inquiry becomes sincere and steadfast. I know

that Dr. S. Bhagvantham, the eminent physicist of India,

and for some time, scientific adviser to the Ministry of

Defence, Government of India, sat at His feet with

notebook in hand, recording the answers he received for

metaphysical questions that troubled him. The

last request that Karanjia presented before Swami was for

confirming his conclusion: "Your Avatâr has

as its aim the restoration of divine consciousness in

mankind". Swami's reply is profoundly inspiring and

illuminating. In the

dream stage, on the other hand, he has no contact with

the world; the senses are silent. Man is then in the

sub-conscious plane. Swami says that every action of ours

produces a corresponding reaction, which is collected and

recollected by the mind. The mind too, like a gramophone

record with shallow grooves scratched upon it, bears the

impression of all that we have suffered, the bouquets and

the brickbats. They lie dormant but (as a needle from the

soundbox runs through the grooves of the record, the

songs and the sobs, the ups and the downs of varied

intensity emerge alive and aloud), the mind is activated

while we sleep. It begins to weave its fantastic imagery

unhindered by the limitations of time and space and

logic. The submerged effects of karma float up

from the unconscious into the sub-conscious and present

themselves as symbols and phantasms. In other words,

impressions of the various desires we have entertained,

concretise before us donning tolerable costumes and

passable conduct. Caught between wakefulness and sleep,

man has to journey through this fog, whether in the role

of victim or witness. The

dream flits in a few seconds all over the world and even

beyond. We are juvenile one moment, senile the next.

Swami describes this make-belief thus: 'At the moment,

you are in this Auditorium among all these people.

Tonight when you dream, you may see this very scene

again, see yourself sitting in the midst of the crowd

listening to my words. But during the dream, it is not

that you are in the Auditorium among thousands but that

the Auditorium and the thousands are in you! The dream

however is as real to you at that time as this event

happening now when you are awake. This 'daydream'

therefore is not more real than the 'dream at

night'.' Let us

go back into the 'thought', 'the will' that prompted the

Non-Being to appear as Being and the Being to Become the

Many so that It may be loved and understood through that

Love. The Being assumed the Cosmic Mind or

Mâyâ in order to diversify Itself and

appear as the Many. This primal Mind persists in everyone

of the Many and plays its tricks of

Mâyâ. We can escape it only by merging

in pure Being, uncontaminated by wish, desire, thought or

will. During the waking stage, Mâyâ or

Mind has many accomplices (the senses, the intellect,

etc.) to help it to delude us. While dreaming, however,

the Mind is the sole actor. It uses the materials stored

in its vaults and continues its game of cheating us into

believing that the Appearance is the Reality. As we know,

the day-dream and the dream at night seem equally real,

at the time we experience them. During dreams we laugh

and weep, sweat and shriek. We can see, therefore, that

it is the mind that possesses the power to project

convincing images and impregnate them with the stamp of

reality. And indeed it can certainly do so for is not

each mind a replica of the cosmic mind? But

when man migrates into the third stage, that of dreamless

sleep, the mind is ostracised, as a diverting deleterious

disturber. The I is then alone with the I. It has no body

to cater to, no senses to run on its errands, no mind to

lead or mislead it. Even the awareness of not being aware

of the outer and inner worlds emerges only when sleep

ends. The ego - the body-mind-intellect complex -

disappears at the onset of sleep. Then, sceptre and crown

do tumble down with plough and pen; everyone is alone

with the Universal One, when the merciful leveller,

sleep, leadens the lids. 'Nidra,

samadhi sthithi,' declares the sage. 'Sleep is the

ultimate stage of equanimity'. Except for the tiny

defect that at that time there is no awareness of the

ecstasy that has descended when the mind was eliminated,

sleep is verily a daily preview of the Summum Bonum

(S.B.

Canto 10).

It merges the Self (divested of the non-Self) in the very

source. What is

that knowledge? Man spends a whole life-time trying to

gather knowledge about the external world, to question

everything around him. But Swami points out that man's

eagerness to know must first begin with none other than

himself. "Without a complete understanding of your own

self, how can you use that instrument (yourself) through

which you try to measure and guage, to examine and judge

all others?" The

real truth, as all religions say, is that, having

understood oneself, all else in the universe can be

known. Man contains within himself all that is found

outside. This fact is rarely understood; so, man neglects

the study of his own 'self'. He spends all his time

struggling to know the 'non-self'. Swami proclaims that

He is God come as man; He reveals, in same breath and

with equal emphasis, that we are also God. God said, "I

am One, let me become Many." "What does 'Many' mean?"

Swami asks. A hundred, for example, is 'many' of course,

but a hundred is really a hundred ones, one repeated a

hundred times. So, each of the Many is a complete One in

itself. "You are the Many and each of you is the One that

willed to repeat Itself", Swami says. But

this knowledge, though heard by the ear, cannot be

realised or understood with conviction by those immersed

in mundane matters. As Swami says, it is only in the

intellect, made clear and penetrating through

Gâyatrî Sâdhana, and the mind

purified by Ashthânga Yoga that this truth

can be revealed. The Gâyatrî

is a prayer, to that intelligence which illumines the

universe, to render our faculty of reason luminous. The

Ashthânga Marga is the eight-limbed path of

selfpurification and spiritual advance laid down by the

ancient sage Patañjali

in his Yoga Sûtras. Today, Swami Himself has

commented on these eight, filling each with profound

potency. The book

Prasanthi Vahini

contains His recast of the traditional meanings of these

steps. The

next step is termed Niyama. It is explained by

pundits as austerity, rectitude and study. Swami however

says that its implications are far wider and deeper, for

it involves continuous sustained discipline and

unwavering remembrance and concentration on the Supreme

Self. On the

fourth stage, that of Prânâyâma,

the regulation of breath, however, He has much to say.

"The control of the vital airs and their movement and

momentum has to be practised intelligently, under

constant supervision. But it is most important to keep in

mind that the exercise will yield positive results only

for those who are aware of the world as a transient

amalgam of truth and falsehood. Only a person conscious

of this mystery can command the Prâna (the breath,

the vital energy) to obey his will." One has

therefore to inhale and exhale to the accompaniment of

the mantra 'Soham'. 'Sa' means 'That' (the One

Truth, the Supreme Self) and 'Aham' means 'I' - I Am

That. The inhaled breath is Sa, the Truth. Each breath we

take in must fill us with Truth. The exhaled breath means

the expelling of the unreal, the appearance, the flux.

The exercise of Prânâyâma has

therefore been raised by Swami to a metaphysical

super-biological level. The

fifth stage, Pratyâhâra, requires the

withdrawal of the organs of perception from the trinkets

and gadgets of the objective world in order to focus

awareness on the One that is the source and sustenance of

all that It has become. Swami teaches us that this stage

can be gone through successfully, only when we are

convinced that the external world is

mâyâborn and

mâyâ-sustained, that it has only

mental and not 'funda-mental', validity. Without this

conviction, the mind cannot be led away from the sights

and sounds, tastes and smells that cloud its

activities. Dhyâna,

in course of time fructifies into the final stage, that

of Samâdhi. "Samâdhi," Swami

declares, means 'sama' (same, equal) 'dhi'

(awareness, intelligence) - it is the denial of duality,

the vision of sameness everywhere, becoming the One

without a second. The 'I' has been liberated from the

cocoon which it had spun around itself; it flies out into

the freedom where it belongs, the expanse of the

boundless sky that knows no distinction or

division. The

person who has achieved Samâdhi can never

again return into the cocoon! He is easily recognised;

for, his thought is truth, his action is dharma,

his nature is santhi and his aura is love.

Nevertheless, he is no superior being, standing afar and

apart on a pedestal of his own. The

Gîtâ allots him a task that he cannot

disown, for it happens spontaneously, with no conscious

effort at all; he no longer has any egoism left in him,

(no feeling 'I', nor sense of doer-ship). This task, says

the Gîtâ, is that of promoting the

welfare of all beings, 'sarva bhûta hithe

rathâh.' [See BG

ch. 6, 29-31] Swami

prods each one of us to set our feet on the

Ashthânga Marga and begin the journey to the

Kingdom of God within us. Speaking to a gathering at

Prasanthi Nilayam during Dasara,

1970, He said, "You are Sathya Swarupas, the

embodiments of Truth. That is why I do not address you as

Dear Disciples or Dear Devotees for it would be crediting

you with a status you do not possess. I call you 'Atma

Swarupa', the description that fits you, whether you are

aware of it or not. It is a statement of fact that no

experiment can prove wrong or incomplete or exaggerated.

You are not the vellayya, mallayya or pullayya you

proclaim yourselves. You are the Immortal, the Eternal,

the Ever-pure Atma!" Karunyanandaji

told Swami that he had once sought the blessings of

Mahatma Gandhi before starting his service to orphan

children. "My blessings cannot help you," Gandhi had

replied "Win the blessing of the truth enthroned in your

heart, instead. That alone can endow you with strength;

that alone can save you in times of need." This

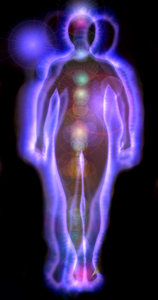

realisation leads him to the awareness of another sheath,

subtler than the physical. This is the

Prânamaya Kos'a, formed of

prâna, the vital air that fills the

Annamaya. This is the basic substance within the

Annamaya and is the reason why this inert machine,

the body, is said to be 'alive'. Prâna performs

five functions that the individual declares are 'his

actions'. These are in-breathing, out-breathing, diffused

breathing, up-breathing and total breathing

(termed

prâna,

apâna,

vyâna,

udâna

and samâna).

When the individual places his faith on his physical body

as his real self, he recognises that other things which

may 'belong' to him but which are not a part of his body

(sons, riches etc.) are not his own 'self'. They are the

'non-self'. When he considers the Prânamaya

kos'a as himself, then the Annamaya sheath is

discarded as a nonself. But it is also foolish to imagine

the Prânamaya to be the self, just as the

gross body was mistaken to be the all. Swami

has disclosed an amazing coordination between the

kos'as which have to be negated and the

cakras

through which the kundalini

energy has to ascend in order to reveal the reality.

Speaking on Raja Yoga during the Summer Course on

Indian Culture and Spirituality, 1977, He said, "The

mûlâdhâra,

the cakra at the lower end of the spinal passage

where the serpent energy lies dormant and coiled is the

seat of the prithivi principle, the terrestrial

(or earth) facet of creation. It is therefore related to

the Annamaya Kos'a. The next cakra, the

svâdhishthâna,

is the guardian of the Prânamaya Kos'a, the

vital sheath. It is the seat of the agni (fire)

element, the source of the warmth in the body which is

engaged in maintaining intact the process of

living. Swami

is the great synthesiser. He reveals the thread on which

various mystic interpretations of yogic exercises are

strung. Man, according to Upanishadic psychology, has

three urges: the urge to act (kriyâ

s'akti), the urge to possess (icchâ

s'akti) and the urge to know (jñâna

s'akti). The Annamaya and

Prânamaya sheaths are activated by

Kriyâ s'akti. The manipâraka

cakra

at the navel which the kundalini reaches next is

also included in the Prânamaya envelope,

since it is the seat of the jalatattva,

(jala = water) the aquatic principle that

regulates and reinforces the circulation of blood and

other internal products. The

sheath that underlies and pervades the Annamaya

and Prânamaya is the Manomaya

Kos'a, the mental or emotional sheath. This

fact becomes evident as the individual progresses in his

efforts at understanding his own astounding make-up. Just

as a piece of cloth is made up of several threads that

criss and cross, so too, mind (manas) is made up

of fancies, impulses, doubts and decisions that are its

warp and woof. But if each thread, that is, each desire,

is pulled out one by one, says Swami, there comes a stage

when the whole piece of cloth, that is the mind,

disappears! This thing we call the 'mind' is just a

bundle of many desires, He reminds us. The

Manomaya Kos'a is the seat of the icchâ

s'akti, the urge to have. The mind is in charge of us

as the sole master when we begin dreaming; it is then

given licence to play its pranks. It builds castles for

our pleasure and caverns and cauldrons for our fright.

And even when we awake, it is the mind that gathers the

information provided by the eyes and ears and parades

them before us for acceptance and appreciation, rejection

or recollection. We are thus at the mercy of its vagaries

as long as we believe the various impulses that agitate

the mind as valid. The

Annamaya Kos'a is predominantly

tâmasic (inertia, darkness) while the

Prânamaya is more râjasic (vibrancy,

passion). The Manomaya sheath however has a slice

of sattva (luminosity, white, pure) in its

composition and so this sheath can, if nursed properly,

lead man to delve into deeper springs of bliss.

Otherwise, the mind is, as the Vajasaneyi

Samhita

warns, a mire of "desire, representation, doubt, faith,

firmness, lack of firmness, shame, reflection, fear." It

is the eleventh sense, the internal motor and motivator.

Its seat is the anâhata

cakra,

centred in the heart region as demarcated by

Yoga. The

seeker however must continue the search for his true

self, must probe deeper than the mind, which is a jumble

of ever-changing thoughts. What an enormous number of

differing, conflicting impulses and emotions have passed

through his mind since the day he was born! How could

these be his real self, the permanent unchanging 'I' that

has throbbed within him despite all the waves of thought

that have come or gone, rolled on and retreated, got

treasured or rejected through all these years? And the

Taittîriya-samhitâ(Upanishad)

says, "Other than the Manomaya, verily other than this

one form of mind, there is another self within formed of

vijñâna (discerning knowledge). By

that, this one is filled."

Vijñâna

[Vijñânamaya Kos'a] is

the ability to examine and decide, the determinative, the

discriminative faculty. The

mind collects many bits of information and converts it

into a thought that forms an impulse for a desire, a

phase of covetousness. It is the discriminative faculty

however that sifts and weighs, judges and resolves. This

faculty is an expression of the jñâna

s'akti, the urge to know. This urge which is innate

in man may progress to intellectual questionings of a

higher order, but ultimately it culminates in the desire

to seek, to reach and to rest in the knowledge of one's

origin and purpose. In a

message He wrote, Swami summarised the whole purpose of

this existence in one brief sentence: "There was no

one to understand Me until I created the world". He

became the Many so that He could have the joy of being

understood or at least, savour the knowledge that a

universal thirst to understand Him pervaded His creation.

This need to always search and know, the

jñâna s'akti is therefore the deepest

driving force in man, that tempts him on to higher and

rarer atmospheres, until he loses himself in the

atmosphere. It is the primal desire that is reflected in

the beneficient trait of vijñâna

(discerning knowledge), the power of discrimination that

leads him in the direction of the last lap of the journey

of evolution. [See also S.B.

3.9] The

mind is helped and liberated when it seeks and allows

itself to be moulded by this inner sheath; but when it

welcomes the impact of the two outer sheaths, it has only

helped itself to be bound even tighter to the trivial and

the temporary. The man who allows

Vijñâna (that is, buddhi, the

intellect, intelligence) to be the charioteer who holds

the reins of manas (the mind), reaches the end of

the journey, says the Upanishad. The

Vijñâna Kos'a has its seat in the

vis'uddhi

cakra

located in the region of the throat. The

Vijñâna principle is an expression of

the âkâs'a (ether, space, one of the

five elements of nature) and hence is all pervasive,

boundless and ever-expanding. When

the inquiry into oneself is pursued further, one

discovers that the urge, behind the urge to know, is an

insistent clamour for joy, for joy that lasts. We learn

from experience that "pleasure is an interval between

two pains" as Swami often reminds us. We bend low

before the blast for the sake of the interval of calm

before we are caught again in another turmoil. We strive

to minimise the pain and maximise the pleasure. The

motivator for this perpetual effort is the last of the

five sheaths, the Ânandamaya Kos'a,

(or blissfull sheath) located in the region of the brow

called the ajñâ

cakra

in Kundalini Yoga. It is the centre which

supervises thoughts and actions. Man is able to glimpse

this truth when he contacts this fringe of the cosmic

consciousness during meditation. He is then

transformed into translucence. The Prasanthi

('abode of extreme peace') he is approaching heralds

itself as Prakanthi (radiance, spiritual

effulgence), the splendor that illumines all the

sheaths. The

word 'maya' (the 'a' is short, not long) means

'composed of', 'saturated with', 'characterised by'.

'Ânandamaya' should not be mistaken for

Brahman which is Ânanda Itself. The

Ânandamaya Kos'a, which we discover as we

continue with the inquiry, envelopes something more

precious. This sheath too has to be surpassed and subdued

before the search can end. Swami assures us that "This

Kos'a is only a step away from the final realisation, the

consummation of all sâdhana and all search,

which is the completion of the unfolding of the kundalini

energy in the thousand spoked wheel (sahasrâra

cakra),

the thousand petalled Lotus (sahasrâdala

padma) on the crown of the head." "Therefore,"

commands Swami, "Delve into yourselves. Investigate.

Discover who you are. No one keeps gold in a gold box,"

He explains, "Steel safes are preferred. So too, the most

precious âtmâ, as eternal, as luminous

as the original paramâtmâ itself, is

kept secure deep within a casket that has five outer

lids." We must plunge and probe, for, great treasures are

never left lying around within reach of undeserving

hands. "So, turn your minds within," He urged in a letter

written to the students of the S'rî Sathya Sai

College at Brindavan, "Find the everlasting basis there,

the supreme source of love, happiness and peace. Everyone

of you is embodied divinity. Your true being is

sat-cit-ânanda (eternity, consciousness,

bliss). You have forgotten this truth. Remember it now

and take the holy and powerful name of the reality, until

your mind disappears and you stand revealed as truth.

Then, enjoy, as Sai has been enjoying, the eternal bliss

which can never be exhausted." In

another message Swami makes the truth clear. "Within you

is the real happiness. Within you is the mighty ocean of

nectar-divine. Seek it within you. Feel it. Feel it. It

is there, the Self. It is not the body, the mind, the

brain, the intellect. It is not the urge of desires; it

is not the object of desire. Above all these, You are.

All else are manifestations. You yourself appear as the

smiling flower, the twinkling star. " Why do

we long to expand our understanding, to enlarge our

horizon, to extend the circle of our acquaintances?

Because we are manifestations of the Omniwill that

willed the same. Why are we curious to uncover secrets,

to unravel mysteries, to peer into the unknown and even

to know about how the known was known? This insatiable

urge to know is but the primal desire to soar up into our

source whose nature is limitless existence, absolute

knowledge and infinite happiness, a desire to reach home

and rest. In fact, we are 'at home' always and

unaffected by restlessness! This

primal search for deathless rest is the gnaw that never

lets us stop or drop by the wayside, the insistent

whisper "Never, never say die!" from somewhere within. It

is the spirit that tells the fish how to feed on smaller

fry to survive. It is the spirit that patiently stripes

the coat of every tiger and spots the skin of every

leopard, the camouflage that helps them blend into their

environment and saves them from killer claws and teeth.

It is this spirit that adds beauty, utility, sweetness to

the tree when it spreads wide the green of its leaves and

the gold of its flowers and paints the earth with the

serenity of its shade. This universal search for

immortality, for truth, peace and love lights our way, as

we tramp back home. The instinct of survival gives us the

chance to march on; the instinct of beauty brings hope

and comfort on the road; and when this spirit grows into

a deep thirst for pure joy, the far turret of that goal

of eternal bliss is sighted; though entangled in

counterfeit pleasure in this pursuit of joy, some

inevitable day, our struggle will draw the Compassionate

Guide towards us, He who will reveal where and how we are

to look for that Joy which we have searched so

long. Once,

when the organiser of a conference asked Swami for a

message, Swami, seizing a piece of paper, wrote, "You,

as body, mind and soul (spirit) are a dream. What you

really are is sat-cit-ânanda (existence - knowledge

- bliss). You are the God of this universe. You create

the whole universe and then you draw it in again. But to

gain, to reach that expanse of the infinite universal

individuality, this cage, the miserable little personal

individuality (the ego) must go." V.S.

Page writes in "Dialogues

with the Divine"

that he asked Swami about the dissolution of the mind. He

doubted the statement made by Swami that mind is

basically inert and questioned, "How can it become

active, then?" Swami replied, "Look! When water is

exposed to the sun, it gets heated and you see in it the

reflection of the sun. The mind reflects the soul

(âtmâ), the pure consciousness and,

therefore, appears to be sentient. The water glitters;

the mind acts. Water is heated; mind is restless. Water

contacts the sun; mind contacts the

âtmâ." Page asked, "Just as we see the

sun in the sky, quite separate from the water, can we

experience the soul distinctly, aloof from the mind?"

Swami said "No! When you experience the

âtmâ, there is no mind. When the hot

rays of the sun evaporate the water, the activity ends

and the reflection disappears. Only the sun remains.

Meditation on the soul makes the mind vanish. This is

"mana-nash", the extinction of the mind, of

desire, of mâyâ, the achievement of

liberation itself". A

doctor from Nigeria asked Swami, "What shall I do to

prevent re-birth?" He writes that he received the reply,

"Do away with desires and ego. See God in all. Love

all. If you do this, one day you will become one with

Me". The advice, in short, was to extinguish the

mind. Swami has told us to bypass the mind

systematically, refusing to cater to its demands, and

refraining from acting in accordance with its wayward

wishes. "Watch its pranks and somersaults, its moods

and motions, with majestic unconcern". The mind will

no longer function as your master; it can be handled as a

tool which can be cast away, after use. This

was the advice Swami gave to the septuagenarian (a person

who is from 70 to 79 years old) monk, Abhedananda, at the

âs'ram of Ramana Maharshi when he

longed for deliverance from the vile vagaries of his

mind. Arjuna pleaded his inability to subdue the

formidable fickleness of the mind. Krishna's prescription

was an attitude of non-involvement, confirming oneself in

this posture by means of relentless practice. Sanity is

recovered when the mind is subdued, the veil is torn, the

lid is lifted, the fog is wafted and one is aware of the

identity of being 'one-self', where there is no second.

As Swami reminds us often, the second one is only the

first one repeated again. It is identical to the truth

that is proved every day of our lives when we see that

every seed or each baby that grows to maturity in no way

loses the complete tree-ness or human-ness the parent

possessed. This very important truth is proclaimed in the

Upanishads

thus: "That is Full. This is Full. From the Full

emerges the Full. When the Full is taken from the Full,

the Full remains Full" "I

am in you. You are in Me. We cannot be separated. Don't

forget that I am always with you. Even when you do not

believe in Me, even when I seem to be on the opposite

side of the earth..." He

repeated these words again with emphasis when Samuel

Sandweiss pleaded to be allowed to live beside Him at

Prasanthi

Nilayam.

"I am always with you, always, always, always! The

distance between us lies only in your imagination."

Once, a

gentleman named Mehta from the âs'ram of

âcârya Vinoba Bhave stood

thunderstruck as Swami spoke to him of long forgotten

incidents, some half formulated plans and projects he had

played with, in his mind in the past. "What is the

sâdhana that gives you the power to read my

past and discover these details?" he asked in amazement.

"Sâdhana?" Swami smiled back, "Why, I am in you

always. You cannot exercise your mind without me! I know

things about you which you do not know yet!" Swami

instils faith and courage in His devotees to know that

they certainly can attain prasanthi, the peace

supreme that is the source of bliss.

Prasanthi

is the end of the path of pariprasna along which

the jijñâsu journeys. He penetrates

the three states (of consciousness) and the five sheaths

with his concentrated relentless questioning: The

wave, Swami has said, rolls and rears, dances with the

wind, dashes forward and retreats back, basks in the sun,

leaps towards the sky, overleaps its kin, frisks in the

rain, all the while believing that it is itself. It does

not know itself as that very sea on which it sports

dressed in a wavy form and distinguished from the source

by a four-lettered name. Until this awareness is gained,

it will be tossed up and down and torn into spray. But

when the truth is known, the agitation ends in calm and

Prasanthi

reigns supreme. The

S'rîmad Bhâgavatam about kos'as: Image

by: souldeep

tad

viddhi pranipâtena:

...

understand that by exercising respect ...

[B.G.

4:34].

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Nagaswaram

flute

![]()

" Kriti 'Yenna Tavam' "

![]()

'The serpent can be tamed and its poisonous fangs

removed, when music from the

Nagaswaram pipe is played and when it is fascinated by

that sweet melody.

The poison that vishaya (object of sensory perception)

exerts on the human mind

can also be eliminated and countermanded,

when man is fascinated by the sweet melodies of

namasmarana or sankîrtan,

that is to say, by the repetitive chanting of the

meaningful Names of the Lord.

The poison in both can thus be transmuted into pure

nectar' -

Sathya Sai Baba

Swami:

Have you ever been to the cinema?

Bhakta:

Ever

been! Why, Swami, the cinema is an essential part of the

world today. Of course I have been to see many films.

Swami:

Tell me then what you saw.

Bhakta:

Oh,

many wonderful pictures, so many voices and noises and

incidents of joy and sorrow.

Swami:

You say, 'I have seen.' Well, the screen is one thing and

the picture another. Did you see both?

Bhakta:

Yes.

Swami:

Did you see both at the same time?

Bhakta:

No!

How could that be possible Swami! When the picture is on,

the screen isn't visible and when the screen is seen, no

pictures are visible.

Swami:

Right!

The screen, the picture - do they always exist?

Bhakta:

The

picture comes and goes but the screen continues to

exist.

Swami:

Yes, the screen is nithya (eternal) and the

picture a-nithya. Now tell me, does the picture

fall on the screen or the screen fall on the picture?

Which is the basis?

Bhakta:

The

picture falls on the screen. The screen is the basis.

Swami:

So,

the external world, the objective world, which is the

picture comes and goes but the internal world, the

âtmâ, which is

existence-awareness-bliss

(asthi-bhâthi-priyam) is the basis. This

'name-form-world' is real only when you witness it or

experience it with your senses, mind and intellect.

Bhakta:

Existence-awareness-bliss? What is that? Swami, give me

an example, if there is any.

Swami:

My

dear boy! Why do you say 'if there is any'? When all is

Brahman, which one thing is not an example? Take

the film. The picture exists, persists, on the screen.

That is the asthi. Who sees it and understands it?

You. You are aware of it. That is bhâthi.

And the names and forms you see are capable of giving

ânanda, that is they are priyam.

Bhakta:

It is clear now, Swami.

Swami:

One point has to be noted here. The pictures fall on the

screen by means of a beam of light projected through a

slit in the wall of the machine-room. But if the light

pours out from the whole room without the slit, the

figures cannot be seen as such, for the screen would be

bathed in light. So, too, when the world is seen through

the small slit of one's mind, the multi-colored

manifoldness of creation is cognisable. But when the

floodlight of atmic awareness is shed, no individual, no

distinction and no disparity is recognised. All is then

cognised as the One Indivisible Brahmam. Have you

understood?

Bhakta:

Yes, Swami, I have understood it clearly.

'Jñânadeva thu Kaivalyam' -

'Liberation is only through the illumination of

awareness' and

'Sraddha-avaan labhathe jñânam' - 'That

illumination is gained by steady faith'.

And it is Jñâna, the third and last

section of the Vedas that is presented as the

culmination of the first two on karma and

upasana. Karma, action, leads to

upasana, dedication. Then, the heart cleansed and

chastened by both these is ready for

jñâna. This section on

jñâna is known as the

Vedânta (knowledge-end), the end of the

Vedas. Vedânta is propounded in the

Upanishad texts, mostly as answers to questions

from seekers and sadhaks.

Swami

welcomes inquiry even into His almighty mystery.

"Come, see, examine, experience and, then,

believe." He does not accept blind faith. In order to

plant the sapling of faith in the hearts of man, and feed

them with love and understanding, Swami has brought out

in book form, the "Prasnottara

Vahini"

(Stream of Question and Answer) wherein He answers more

than two hundred queries, on physical, mental, social,

familial, moral and spiritual problems. Swami elicits

from the persons sitting around Him during what are

commonly known as 'Interviews' (though an aged monk named

Gayathri Swami refused to refer to it as anything other

than a Centreview), their hidden pains and hurtful

dilemmas. Exposed to the sunlight of His sublime sympathy

and love, they are all rendered harmless. The

Upanishad assures us that the impact of wisdom and

love results in "loosening the knots in the heart and

shattering the doubts in the mind". Dr. Hislop has

recorded in "Conversations with Bhagavân

S'rî Sathya Sai Baba" a few occasions, in the

interview room and other locations of such diagnosis and

cure. Mr. V.S. Page was encouraged by Swami to seek

clarification on the validity of certain spiritual

experiences, when members of the Maharastra Branch of

Bhagavan-Sponsored Academy of Vedic scholars gathered

around Him. The questions and answers have been published

in the book "Dialogues

with the Divine".

Swami

welcomes inquiry even into His almighty mystery.

"Come, see, examine, experience and, then,

believe." He does not accept blind faith. In order to

plant the sapling of faith in the hearts of man, and feed

them with love and understanding, Swami has brought out

in book form, the "Prasnottara

Vahini"

(Stream of Question and Answer) wherein He answers more

than two hundred queries, on physical, mental, social,

familial, moral and spiritual problems. Swami elicits

from the persons sitting around Him during what are

commonly known as 'Interviews' (though an aged monk named

Gayathri Swami refused to refer to it as anything other

than a Centreview), their hidden pains and hurtful

dilemmas. Exposed to the sunlight of His sublime sympathy

and love, they are all rendered harmless. The

Upanishad assures us that the impact of wisdom and

love results in "loosening the knots in the heart and

shattering the doubts in the mind". Dr. Hislop has

recorded in "Conversations with Bhagavân

S'rî Sathya Sai Baba" a few occasions, in the

interview room and other locations of such diagnosis and

cure. Mr. V.S. Page was encouraged by Swami to seek

clarification on the validity of certain spiritual

experiences, when members of the Maharastra Branch of

Bhagavan-Sponsored Academy of Vedic scholars gathered

around Him. The questions and answers have been published

in the book "Dialogues

with the Divine".

(1) When the devotee is convinced, 'I am entirely

Yours';

(2) When he is firm in the faith, "You are entirely

mine";

(3) When he is no longer I and has merged in 'You', the

source and sum of all ' I's '.

"Likewise", Swami added, "a jñâni

also has three phases in his spiritual life:

(1) Soham: I am He

(2) Aham Sah: He is I, and

(3) Aham eva aham: I am I.

The final stages of both the bhakta and the

jñâni are not different from each other.

They represent the mergence in one unitive cosmic

consciousness.

Âsana

or posture is the third anga (limb). Swami does not

elaborate on the various physical contortions and

gymnastics recommended by the teachers of Yoga but

merely says that the udasin, the relaxed

effortless posture, free from strain or tension, is the

one that is best.

Âsana

or posture is the third anga (limb). Swami does not

elaborate on the various physical contortions and

gymnastics recommended by the teachers of Yoga but

merely says that the udasin, the relaxed

effortless posture, free from strain or tension, is the

one that is best. The

next stage that Patañjali prescribes is

Dhâranâ (concentration or

steadfastness), the fixing of the consciousness

(citta) on a single elevating thought. Swami

clarifies the modus operandi of this effort thus:

"Treat the citta as a child, as a toddler. Caress it

and win its love and trust. Lead it with tender sympathy,

remove its fears and falterings with soft reprimands and

focus its attention always on the beauty of truth."

Once the aspirant has superseded his sense organs by

understanding the falsity of what they portray as 'real'

(pratyâhâra), his mind will be steady,

concentrating on the One, beyond all this variety of

appearance (dhâranâ) and he then slips

easily and effortlessly into the seventh stage of

Dhyâna, meditation. Swami defines this stage

as "the uninterrupted dwelling of one's consciousness

in the Cosmic Consciousness". That is to say,

concentration achieves such constancy that he himself

grows unaware of the fact that he is engaged in

meditation. He does not have to force his mind to remain

fixed on one elevating thought, for, steadfastness now

becomes as natural, as incessant and as vibrant for him

as breathing itself.

The

next stage that Patañjali prescribes is

Dhâranâ (concentration or

steadfastness), the fixing of the consciousness

(citta) on a single elevating thought. Swami

clarifies the modus operandi of this effort thus:

"Treat the citta as a child, as a toddler. Caress it

and win its love and trust. Lead it with tender sympathy,

remove its fears and falterings with soft reprimands and

focus its attention always on the beauty of truth."

Once the aspirant has superseded his sense organs by

understanding the falsity of what they portray as 'real'

(pratyâhâra), his mind will be steady,

concentrating on the One, beyond all this variety of

appearance (dhâranâ) and he then slips

easily and effortlessly into the seventh stage of

Dhyâna, meditation. Swami defines this stage

as "the uninterrupted dwelling of one's consciousness

in the Cosmic Consciousness". That is to say,

concentration achieves such constancy that he himself

grows unaware of the fact that he is engaged in

meditation. He does not have to force his mind to remain

fixed on one elevating thought, for, steadfastness now

becomes as natural, as incessant and as vibrant for him

as breathing itself. The

first sheath and the most obvious one is the

Annamaya Kos'a, this physical body

sustained by the food we eat; this cage in which we dwell

and which we carry about with us from birth to death.

Ramana Maharishi, in his later years, used to

complain, "How long am I, singly, to carry around this I

body which has to be placed on the shoulders of four

others?" (that is, when it is carried as a corpse to the

cremation grounds). The aspirant is encouraged to

contemplate on all the component parts of the body - the

brain, the heart, the blood, the bone, the genes - all

thriving on the calories and the chemical we take in, and

on the various functions of the body connected with this

food - the assimilation of nourishment, the circulation

of blood, the elimination of waste. When he thus divides

the body and examines its individual part and functions,

he realises that it is just a complex machine carrying

out certain assignments automatically. It cannot be

mistaken for the spirit of life, for the yearning and

intuition burning within, for the sense of 'I', of which

he is ever-conscious.

The

first sheath and the most obvious one is the

Annamaya Kos'a, this physical body

sustained by the food we eat; this cage in which we dwell

and which we carry about with us from birth to death.

Ramana Maharishi, in his later years, used to

complain, "How long am I, singly, to carry around this I

body which has to be placed on the shoulders of four

others?" (that is, when it is carried as a corpse to the

cremation grounds). The aspirant is encouraged to

contemplate on all the component parts of the body - the

brain, the heart, the blood, the bone, the genes - all

thriving on the calories and the chemical we take in, and

on the various functions of the body connected with this

food - the assimilation of nourishment, the circulation

of blood, the elimination of waste. When he thus divides

the body and examines its individual part and functions,

he realises that it is just a complex machine carrying

out certain assignments automatically. It cannot be

mistaken for the spirit of life, for the yearning and

intuition burning within, for the sense of 'I', of which

he is ever-conscious.

![]()

![]() "

Rama Neel Amegha Shyama

"

"

Rama Neel Amegha Shyama

" ![]()

text

bhajan

- Koham? (who am I?)

- Dehoham? (Am I the body?)

- Dâsoham? (Am I a servant, a tool, a puppet?)

- Soham? (Am I He?) - until there comes that moment when,

in a flash, he is rewarded with the answer beyond which

no more questions lie:

Thath Thwam Asi - That Thou Art!

that there is neither I nor He but, as Swami announces

"I am you; you are I. Know that I and He do not become

We. I and He are never separate. Only ONE ever was, is

and will be."

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

- 2.1:25

/ This outer shell of the universe known as a body with

seven coverings [fire, water, earth, sky, ego,

noumenon and phenomenon, see also kos'as], is the

conception of the object of the Universal Form of the

purusha as the Supreme Lord.

- 3.29:40-45

/ Of whom out of fear the wind blows and out of fear this

sun is shining, of whom out of fear rains are sent by the

Godhead and of whom out of fear the heavenly bodies are

shining, because of whom the trees and the creepers do

fear and the herbs each in their own time bear flowers as

also fruit appears, the fearful rivers flow and the

oceans do not overflow, because of whom the fire burns

and the earth with its mountains doesn't sink out of fear

for Him, of whom the sky gives air to the ones who

breathe, under the control of whom the universe expands

its body of the complete reality

[mahâ-tattva] with its seven layers

[the seven kos'as or also dvipas with their states of

consciousness at the level of the physical,

physiological, psychological, intellectual, the enjoying,

the consciousness and the true self.], out of fear

for whom the gods in charge of the modes of nature of

this world concerning the matters of the creation carry

out their functions according to the yugas [see

3-11], of whom all this animated and inanimate is

under control; that infinite final operator of

beginningless Time is the unchangeable creator creating

people out of people and ending the rule of death by

means of death.

- 10.87:17

/ They who bellow as if they are breathing [see B.G.

18.61] are really alive if they are Your faithful

followers, for You, above cause and effect, are the

underlying reality of Whose mercy the universal egg of

the totality, the separateness and the other elements of

the person was produced [see 3.26: 51-53]; with

You, according to the particular forms they furthermore

lead to, appearing among these as the Ultimate One in

relation to the [mere] physical coverings and so

on [the kos'as and B.G. 18: 54].

prâna:

Life force, vital energy, breath.

apâna:

One of the five vital energies which moves in the

lower trunk controlling elimination of urine, semen and

faeces.

vyâna:

One of the

vital energies pervading

the entire body distributing the energy from the breath

and food through the arteries, veins and nerves.

udâna:

One of the five

principal vâyus (vital energies), situated in the

throat region which controls the vocal cords and intake

of air and food.

samâna:

One of the vâyus, vital energy which aids

digestion.

cakra: Energy centres situated

inside the spinal column.

kundalini: Divine cosmic

energy.

mûlâdhâra

cakra: Energy centre situated at the root of the

spine.

svâdhishthâna

cakra: Energy centre situated above the organ of

generation.

manipâraka cakra: Energy

centre at the navel area.

vis'uddhi cakra:

Energy centre situated behind the throat region.

ajñâ cakra:

Energy centre situated between the centre of the two

eyebrows.

sahasrâra

cakra: cakra or energy centre situated at the crown

of the head, symbolized by thousand-petalled lotus.

kriyâ: Action, execution,

practice, accomplishment

s'akti: Power, capacity,

faculty.

icchâ: To cause to desire,

will.

jñâna: Knowing,

knowledge, cognizance, wisdom.

anâhata cakra:

Energy centre situated in the seat of the heart.

Vajasaneyi-samhitâ:

- The Shukla Yajurveda Samhita also known as the

Vajasaneyi Samhita, is said to have been collected

and edited by the famous sage Yajnavalkya.

- The Purusha Sukta is an important part of the Rig-veda

(10.7.90.1-16). It also appears in the Taittiriya

Aranyaka (3.12,13), the Vajasaneyi Samhita

(31.1-6), the Sama-veda Samhita (6.4), and the

Atharva-veda Samhita (19.6). An explanation of parts of

it can also be found in the Shatapatha Brahman, the

Taittiriya Brahmana, and the Shvetashvatara

Upanishad.

-The Purusha Suktam is seen earliest in the Rg Veda, as

the 90th Suktam of its 10th mandalam, with 16 mantrams.

Later, it is seen in the Vajasaneyi Samhita of the Shukla

Yajur Vedam, the Taittriya Aranyaka of the Krishna Yajur

Vedam, the Sama Veda, and the Atharvana Veda, with some

modifications and redactions. See

also Yayurveda.

Taittirîya-samhitâ:

(S.B.

12.6:64-65)

The son of Devaratâ then regurgitated the collected

Yajur mantras and left from there. The sages greedily

looking at these Yajur mantras, turning into partridges

picked them up; thus became these branches of the

Yayur-veda known as the most beautiful

Taittirîya-samhitâ ['the partridge

collection'].

Annamaya Kos'a: Anatomical body

of man.

Prânamaya Kos'a: The vital body, organic

sheath of the body.

Manomaya Kos'a: The mental or the emotional

sheath.

Vijñânamaya Kos'a: The intellectual

or discriminative body.

Ânandamaya Kos'a: The blissful sheath.

Turîya: the

superconscious state of the soul its selfrealization (see

S.B.

12.11:22).